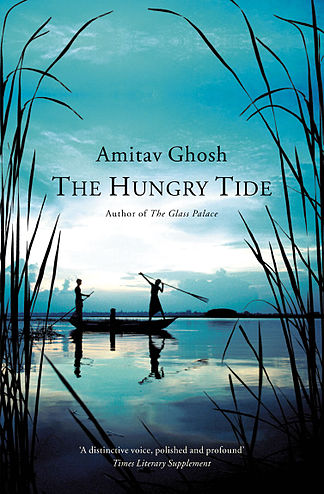

Amitav Ghosh is not for everyone. He is one amongst the very notably present Indian writers who write in English. Most of the journey through his work is an attribution to time and space and ‘The Hungry Tide’ is exactly the kind of expedition one can look for if they seek for history and memories. Ghosh rejects the rectilinear pattern and carries you to another world, criss-crossing through events to let you live tales of home and homelessness in ‘The Hungry Tide’.

Publisher : HarperCollins, pp400

Sweeping off your feet, and into the indefensible waters of the Sundarbans, this story takes the readers to the tide country for a voyage to the archipelago of islands of Bay of Bengal. Ghosh traces some deep-rooted issues like freedom, conflict, refugees, government, and oppression in the backdrop of the lives of the characters in the book, namely, Piya, Fokir and Kanai, and Nirmal from the past, all of who appeal the unawares into the prevailing political tinges of this secluded bend of the world.

Being a native of Bengal, I have not yet visited Sundarbans, but Ghosh definitely knows where to pinch. ‘The Hungry Tide’ is not for a marked audience and no matter where you stay, you would know what it feels like to crush your toes in the silky mud, how the tips of your fingers feel to touch the mangrove roots and what it is like to have lived and dealt with fear.

Piya is a cetologist, who in search of the rare dolphins, Orcaella, roots for her mission to Sundarbans. She is an American with Bengali lineage but someone who remembers her mother tongue solely as the language her parents quarreled in. “There was a time when the Bengali language was an angry flood trying to break down her door. She would crawl into a closet and lock herself in, stuffing her ears to shut out those sounds. But a door was no defense against her parents’ voices: it was in that language that they fought, and the sounds of their quarrels would always find ways of trickling in under the door and through the cracks, the level rising until she thought she would drown in the flood.. The accumulated resentments of their life were always phrased in the language, so that for her its sound had come to represent the music of unhappiness.” Although Piya seems to have eventually sought peace in the impartial discourse of science rather than emotionally dwelling in the soul of language, Kanai, who bumps into her on a train, seems to have found a familiar chord with her for her reflection of the depth of her research “like a textual scholar”. Kanai, on the other hand is a little self-consumed businessman who leaves his passion for Bengali Poetry to set up an interpretation agency in New Delhi. Ghosh also weaves an intricate link between Fokir, the simple boatman, Piya and Kanai. The most delightful part of the story is the inconspicuous connection between Fokir and Piya who develop the best part of the novel with their indifference to any cultural or linguistic barrier ruling their common yearning to unfold the secrets of the river. Lack of words is compensated with the strength in silence and glance that shames the practical differences between them.

Kanai, on the other hand, returns to his homeland in the Sundarbans for the exception of his aunt’s request to receive his late uncle, Nirmal’s gift in the form of a journal in his diary that narrates the personal history of the tide country. Nirmal is a once-radical communist who defines home as an attachment to the causes which he can identify himself with. One such cause is the struggle of the settlers of Marichjhapi, which was a administrative butchery of Bangladeshi refugees during the years 1940s and 1970s, in the face of government oppression. Nilima, his wife, has a difference of opinion on this matter and she considers him as a melancholic schoolteacher and intends how his heart was never really where ‘home’ was, as she goes on to say, “(He) was in love with the idea of revolution. Men like that, even when they turn their backs on their party and their comrades, can never let go of the idea: it’s the secret god that rules their hearts. It is what makes them come alive; they revel in the danger, the exquisite pain. It is to them what childbirth is to a woman, or war to a mercenary.” But it is Nirmal’s fascinating character and his narration that makes his life a parallel novel inside a novel.

Although Ghosh sets a standard for elegance with this piece, however, what refused to appeal was the impression that either of the main characters would have expected any kind of romantic involvement with each other. It is not convincing. Also, at some point, Kanai’s presence in the book stops making sense beyond his functionality.

But I could see what Ghosh has done with the work and why it makes sense to admit that this led him to write the Booker Prize winner, Sea of Poppies Trilogy.